In 1803, a young man ran away from his home in Salem, Massachusetts. He was only thirteen, but even at that young age the sea called to him as the mythical Sirens had lured the ancient mariners. Like other young men of his age, his life as a sailor began as a cabin boy. By the time he was twenty-one, he qualified as a master mariner and commander of his own ship, the Charles Doggett.

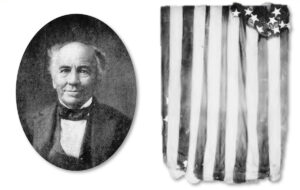

Before setting sail for his first voyage as a ship’s commander, his mother and a group of young girls presented him with a gift – a hand-sewn, homemade American flag fashioned to be hoisted on his ship. Legend has it that when the flag was unfurled, Driver immediately named her “Old Glory.” Others claim he coined the term later in his life, but either way, a new phrase entered the American lexicon.

Seven years later, Driver’s ship was the last of six vessels departing from Salem for the South Pacific and eventually escorted sixty-five descendants of the survivors of the HMS Bounty from Tahiti back to their homes on Pitcairn Island. Driver retired from the sea in 1837, concluding a twenty-year career that carried him to China, India and other exotic countries around the world, finally settling in Nashville, Tennessee, to raise his twelve children.

Every holiday, Driver would raise “Old Glory” outside of his house, strewn from his attic window to a locust tree across the street. One of his daughters remembers her sisters, Driver and his wife sewing additional ten stars to the flag, reflecting the expansion of the United States. But as tensions escalated across the country and talk of secession spread throughout the South, Driver’s flag became a source of division. While Driver remained loyal to the Union, two of his sons joined the Confederate Army, one never to return home.

After Tennessee seceded, Confederates attempted to seize Old Glory, at one point sending an armed guard to search the house. However, Driver was ready for them and had his treasured flag sown into a quilt where it remained hidden until February 1862 when Nashville was occupied by Union troops. Seeing the flag of the Sixth Ohio Regiment raised over the capitol, Driver made his way to meet the Union commander, carrying on his arm “a calico-covered bedquilt.” Ripping open the quilt, with tears in his eyes Driver presented Old Glory to Union General William Nelson who ordered it to be run up on the capitol’s flagstaff. The regiment adopted “Old Grory” as its motto.

The war was far from over as the Confederate Army attempted to retake the city. Driver participated in its defense and continued to display Old Glory, threatening to blow up his whole house if she was not hanging in plain sight when he returned.

Years later, after Driver’s death in 1886, a family feud broke out over who owned Old Glory and even which flag was, in fact, Old Glory. Apparently when a storm had threatened to shred the flag to pieces, Driver had hoisted another flag, much stronger and more resistant to the winds of the storm. Some people reported that Driver had once again stored Old Glory for safekeeping. Others claim he gave it to the Sixth Ohio Regiment, while still others said it remained hidden in Driver’s home when the second battle for Nashville began in 1864.

The family feud resulted in two “Old Glory” flags being presented to the Smithsonian Institution, the first by one of Driver’s daughters who had given it to President Warren Harding in 1922. The President offered it to the Smithsonian. But the controversy had started much earlier, within a year of Driver’s death, when a niece claimed to have inherited it and delivered it to the Essex Institute (now the Peabody Essex) in Salem which then forwarded it to the Smithsonian.

Historians and a variety of textile experts and preservationists may or may not resolve the issue, although the weight of the evidence appears to lie on the side of the flag inherited by Driver’s daughter. In any event, “Old Glory” continues to this day as a sentimental and friendly nick-name for the flag to which we pledge our allegiance and honor each year on June 14. On that day, we commemorate the resolution passed by the Second Continental Congress on June, 14, 1777, which declared “that the flag of the thirteen United States be thirteen stripes, alternate red and white; that the union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a new constellation”.