If you write (or go online) to the National Archives, the depository of our country’s historical documents, and request a copy of the original Bill of Rights, also known as the first Ten Amendments to the Constitution, you might be surprised at what you receive. It will be list of twelve, not ten. The fact is, there is no “original” copy of the Bill of Rights composed of ten amendments as we know them. Let me explain.

During the convention that drafted our Constitution and the conventions in the original thirteen states that ratified it, opponents of the Constitution complained that it did not sufficiently protect the rights of the people. Some even proposed convening another convention to propose amendments, including a bill of rights.

James Madison and George Washington were among those who believed a bill of rights was not only unnecessary, but could be disadvantageous to the rights of the people. Because the Constitution provides for a limited government, they argued, government could not touch upon what was not actually included in the Constitution. For example, Roger Sherman of Connecticut noted that an amendment to protect freedom of the press was not needed because “the power of Congress does not extend to the press.” Others asserted that making a list of protected rights could be considered “exhaustive;” that is, rights not listed would not be protected.

In the end, proponents of a bill of rights prevailed. Several states made their ratification contingent on the promise that Congress would propose amendments, including those securing the rights of the people. More than one hundred twenty amendments were eventually proposed.

The first Congress under the new Constitution convened on March 4, 1789. James Madison, having been elected as a member of House of Representatives from Virginia and pledged to support amendments, considered himself “bound by honor and in duty” to adhere to his pledge. On June 8, he introduced a series of proposals in the House which were later hotly debated and eventually reduced to seventeen proposed amendments on August 24.

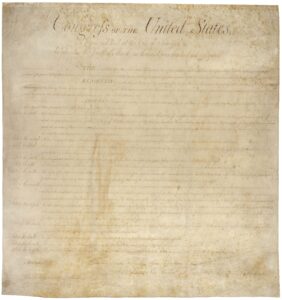

Within a month, the Senate considered the House bill, rejected two of the amendments, and reduced the number from seventeen to twelve. On September 25, the House and Senate passed a Joint Resolution resolving that the twelve proposed amendments be added to the Constitution when ratified by three-fourths of the state legislatures, which at that time meant ten states. Three days later, on September 28, Speaker of the House Frederick Muhlenberg and Vice President John Adams signed the enrolled copy. Thirteen additional copies were created, one for each of the eleven states that had ratified the Constitution, as well as one each for Rhode Island and North Carolina, neither having yet adopted the Constitution.

It is this “enrolled and signed” copy that contains the original bill of rights. So, how did the twelve become ten? It began on November 20, 1789, when the legislature of New Jersey became the first state to ratify the first proposed amendment along with the third through the twelfth. It did not ratify the second on the list. On December 19, Maryland ratified all twelve. A month later, North Carolina (having adopted the Constitution on November 21) ratified all twelve. Other states followed, each one ratifying the third through the twelfth proposed amendments, but some rejected either the first or second proposed amendments.

Rhode Island finally adopted the Constitution on May 29, 1790, and a week later ratified all of the amendments, except the second. On March 4, 1791, Vermont became the 14th state and ratified all of the amendments on November 3 of that year. The same day, Virginia ratified the first of the twelve amendments and on December 15 ratified those remaining.

Virginia’s ratification reached the constitutional goal of three-fourths of the state legislatures needed to ratify ten of the proposed twelve amendments – namely, amendments three through twelve. The result is that the first two proposed amendments had been rejected.

In short, ratification by the states occurred at different times over two years and two of the proposed twelve amendments were not ratified. Therefore, there is not an “original” copy what we know as the Bill of Rights – or the first Ten Amendments to the Constitution.

So, what did the states reject? The first proposed amendment allowed one representative in the House of Representatives for every 50,000 people. It fell short of ratification by one vote. The second proposed amendment prohibited Congress from raising its own pay until the next Congress would be convened. It received approval by only six states…until 1992 when it was ratified by the required number of states after being resurrected in a paper written by Gregory Watson, a student at the University of Texas at Austin. In the early 1980’s Watson had argued that the amendment was still alive and started the amendment ball rolling again.

We now celebrate December 15 as Bill of Rights Day and consider this. The next time someone says the guarantees of free speech, press, religion, etc., are the most important and that is why they are included in the first of the amendments, you might let them know these guarantees were originally included in the third of the proposed amendments. Today’s First Amendment was originally the Third Amendment.

But the most important lesson to be learned from this brief history is this: the Bill of Rights has provided citizens and residents of the United States with the greatest guarantees of freedom and individual rights in human history.