The 25th commemoration of the Declaration of Independence took place on July 4, 1801, only months after its principal author, Thomas Jefferson, was inaugurated as our country’s third president. Parades, horse races, cock fights and tents brimming with food and drink filled the north grounds of the Executive Mansion while the new President met with diplomats, officers, citizens and Cherokee chiefs. The Marine Corps Band, dubbed “the President’s Own” by Jefferson, played in the Entrance Hall.

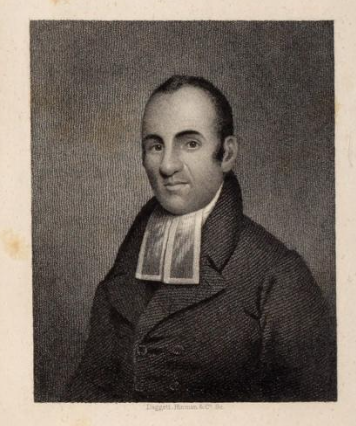

Nearly four hundred miles away, in Rutland, Vermont, a middle-aged Congregationalist minister addressed his congregation. After all, it was Sunday. He had been pastor of the West Parish in Rutland for thirteen years and would remain in that capacity for another seventeen years. He would go on to serve as a pastor in Manchester, Vermont, for four years and then in South Granville, New York, for another eleven years before his death in 1833.

This popular and respected cleric was known for his adherence to Calvinist theology, fidelity to Scripture, and opposition to “universalism,” the belief that all humans would eventually be saved. His polemical homily against universalism was published in more than forty editions. Fluent in Greek and Latin, his sermons demonstrated a thorough understanding of Biblical ethics, including the principles that liberty cannot exist without virtue and that all are created equal and precious in the sight of God. Yet, according to one observer, he “was largely reticent about discussing slavery or politics.”

But today was different. His sermon was titled “The Nature and Importance of True Republicanism, With a Few Suggestions Favorable to Independence.” The moral and natural endowments given to us by our Creator, he said, should be used “in every way wherein we make no encroachments on the equal rights of our neighbor.” The laws should defend these invaluable blessings which “equally belong to all men as their birthright.” This, he continued, “is that genuine republicanism that we ought most earnestly contend for and is the very foundation of true independence.”

Twenty-five years earlier, in 1776, our pastor was a young man who had enlisted as a private in the Continental Army. He had already enlisted in the militia in the aftermath of the clash between militiamen and British Regulars at Lexington and Concord. But his service in the Army was cut short by a bout of typhus. Nevertheless, his enthusiasm for liberty and independence was second only to his love of God, faith in his savior Jesus Christ, and commitment to respect for all of God’s children. It was then, in 1776, years before his ordination as a Christian minister, that he had penned “Liberty Further Extended: Or Free Thoughts on the Illegality of Slave-keeking.”

On the title page of his manuscript, he wrote the most profound statement in the Declaration of Independence, that “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” Because our Creator bestowed freedom on men, he wrote, no man has the right to take it from another; that is a prerogative belonging only to the Creator. Moreover, the right is not confined to any nation, “…even an African has equally as good a right to his liberty in common with Englishmen.” He warned his country to “break these intolerable yokes…for God will not hold you guiltless.”

His extensive essay is founded on Old and New Testament Scriptures, citing specific passages to debunk in detail defenses of slavery and slave-trading, calling them “lame” and “defective.” He called out the hypocrisy of those clamoring for freedom yet held others in bondage. These were precursors to arguments later used by abolitionists and freedom fighters in future decades, including Frederick Douglass and Martin Luther King, Jr.

All of this from a most unlikely Patriot. Lemuel Haynes was born on July 18, 1753, to a black father and white mother in West Hartford, Connecticut. Abandoned by both of his parents, at the age of five months he was taken into indentured servitude by a deeply religious white family who treated him as one of their own. Immersed in family worship and church attendance, he learned to read at a young age, began to memorize Scripture and write sermons, and practice preaching using an old hollow log as a pulpit.

It was when his indenture ended at the age of twenty-one that he enlisted as a militiaman. He learned Latin and Greek while working as a laborer and a schoolteacher to support himself. In 1785, he was the first African American to be ordained as a minister by a mainstream Protestant denomination. In 1804, at Middlebury College, he became the first African American to receive an honorary degree. This remarkable man’s unique distinction was his status as a Black pastor to wholly white congregations. Known as the Black Puritan, he wrote, “liberty is equally as precious to a Black man as it is to a White man, and bondage as equally intolerable to on the one as it is to the other.”