Meeting in the Pennsylvania State House on June 14, 1775, just two months after the battles of Lexington and Concord, the Second Continental Congress voted to create a Continental Army to coordinate the military response of thirteen British colonies to occupying British troops. The next day, George Washington was unanimously elected as its Commander-in-Chief.

Less than a month later, Washington took command of sixteen thousand militia on the outskirts of Boston, charged with creating an army out of inexperienced amateurs and farmers. By mid-October, he had begun to commission ships to protect the shores and sea-lanes of the colonies. Col. Jospeh Reed, an aide-de-camp to Washington, wrote to a Col. Moylan on October 20, advising creation of “some particular color for a flag and a signal by which our vessels may know each other.”

Reed’s own design, a green pine tree on a white background with the words “An Appeal to Heaven” was the first to fly on American ships. But this was not the only standard swaying in the colonial breezes. There was a plethora of designs utilizing stars, stripes, rattle snakes, crescents, pine trees, and other symbols, but none signifying the nascent unity of the colonies.

On January 1, 1776, British troops under the command of Major General William Howe, awakened to the sight of a seventy-six-foot mast standing upright near Boston on Prospect Hill where the Continental Army had constructed fortifications separating the opposing camps. Flying at the top was a flag ordered raised by General Washington who recorded in his diary on January 4, “We gave great joy to [the British] without knowing it or intending it, for on that day which gave being to our new army…we hoisted the Union flag in compliment to the United Colonies.”

That flag, known as the “the Continental Colors” and later as the “Grand Union,” was composed of thirteen alternating red and white stripes with the British Union Jack in the upper left corner. Some interpreted its design as a compromise – the thirteen stripes representing protests of the united colonies and insertion of the Union Jack as a reflection of continued loyalty to the King. Others believed the shrunken size of the Union Jack mocked the diminishing authority of the British over the colonies, while General Howe believed the flag was a sign of colonial submission.

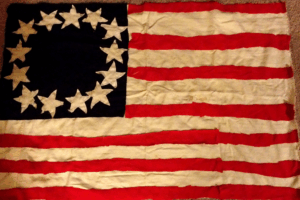

Whatever the interpretation and its lack of “official’ sanction, it was the first true American flag to become a symbol of the new nation. Finally, on June 14, 1777, as Congress considered on-going war measures and planned defenses against an expected attack on Philadelphia, it passed a resolution “that the flag of the thirteen United States be thirteen stripes alternate red and white; that the Union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field representing a new constellation.”

There were no instructions regarding whether the stripes should be horizontal or vertical; nothing about the arrangement of the stars, or even why stars were selected to represent a “new constellation.” Nor were there explanations, other than tradition borne of its English heritage, of why the colors red, white and blue were chosen and if they carried any special meaning. Absence of specific information, combined with crude communications over time and distance, took its toll, resulting in a variety of designs springing up on land and sea.

Moreover, while Betsy Ross may have sown a flag, history has dispelled the myth that she designed the flag composed of thirteen horizontal red and white stripes with thirteen white stars arragned in a circle on a blue field. That was probably the design proposed by Francis Hopkinson. But even that design soon ceased to be an accurate representation of the United States. Vermont joined the Union in 1791, followed by Kentucky in 1792. The next year Congress passed a bill increasing the number of stars and stripes to fifteen. It was that flag which Francis Scott Kay saw flying over Fort McHenry a decade later and inspired him to write the “Star Spangled Banne.”

The United States continued to expand: Tennessee in 1796; Ohio in 1803; Louisiana in 1812; Indiana in 1816. Mississippi would be next. The specter of a flag crowded with increasingly small, thin stripes was untenable. Moreover, it would be difficult to identify at sea. Additionally, there was a strong desire to honor the original thirteen colonies. Finally, Congress acted by passing the Flag Act of 1818. Signed by President James Monroe on April 4 of that year. It provided that the flag of the United States be “thirteen horizontal stripes, alternate red and white” and “on the admission of every new State into the Union, one star shall be added to the union of the flag,” to be added on the next fourth of July after such admission. So has it been since that day.

It would be more than a hundred years before Congress would designate the “Star Spangled Banner” as our official national anthem and another twenty years before officially recognizing the Pledge of Allegiance to that flag.